In answering a standard question of how to write an abstract, it must be mentioned that this element is a first section of any research paper. Basically, readers must understand an author’s work after reviewing a chosen study. On the other hand, it is vital that a person understands how to write this section in order to describe a whole document correctly. As such, an in-depth analysis of abstract authorship focuses on its definition, format, types, examples, and best approaches, being critical concepts that facilitate mastery of research skills.

General Aspects

Abstracts are common segments of academic documents. Basically, these parts are self-contained summaries that are relatively short in length and provide complete primary information about a large study in a brief statement. Further on, a main role of an abstract is to provide a reader with an overview of an entire research paper that identifies the most significant findings. In writing a synopsis section, this part must identify a key reason for an entire study, its problem, methodology, outcome, and implications. As such, people have to address these five areas for any study. Moreover, an author has to provide a necessary attention to particular aspects that magnify critical points of their projects. Hence, scholars must have a basic knowledge of how to write an abstract in an academic field at any level.

What Is an Abstract and Its Purpose

According to its definition, an abstract is a concise and brief summary of a larger work, such as a research paper, proposal, capstone project, thesis, dissertation, case study, or report, that provides an overview of document’s main points, including methodology, results, and conclusions. For example, the main purpose of writing an abstract is to allow people to quickly determine an actual relevance of a full document to their interests or research needs without needing to read an entire work (Hyatt & Roberts, 2024). In writing, this section typically includes key objectives, methodology, findings, and conclusions of a whole work, all within a concise format of about 150-250 words. Further on, abstracts serve as a critical tool for indexing and searchability, helping researchers and professionals to find pertinent studies or reports quickly (Miller, 2023). Basically, such a part of a research paper can highlight an actual significance of an entire study or its findings, guiding a reader’s focus and providing a specific context for a detailed piece of information that follows in a main text. Moreover, by distilling a complex content into a brief and clear format, this writing section enhances accessibility and ensures a core message of a scientific work is conveyed efficiently (Drury et al., 2023). In terms of pages and words, a specific length of an abstract depends on academic levels, specific institutional requirements, and scopes of projects, while general writing guidelines are:

High School

- Length: 1/4-1/2 of a page

- Word Count: 100-150 words

College

- Length: 1/3-1/2 of a page

- Word Count: 150-250 words

University (Undergraduate)

- Length: 1/2-3/4 of a page

- Word Count: 200-300 words

Master’s

- Length: 3/4-1 full page

- Word Count: 250-350 words

Ph.D.

- Length: 1-2 pages

- Word Count: 300-500 words

Types

There are 4 types of abstracts, such as descriptive, critical, informative, and highlight sections.

Descriptive

Descriptive abstracts are approximately 150 words. For example, they explain an entire examination being summarized by mentioning a purpose, methods, and scope without providing any judgments concerning the findings (Hyatt & Roberts, 2024). In writing, a lack of an opinion regarding a given study is an unique quality of descriptive overviews.

Informative

Informative abstracts are similar to descriptive ones. However, they point out primary arguments and evidence, results, conclusions, and recommendations with a 300-word count limit (Burton, 2021). Basically, an informative overview offers a more detailed writing description than a descriptive one.

Critical

Critical abstracts contain interpretive commentary. Basically, this type complements a investigation’s description by providing judgments on an overall completeness or reliability of an observed study (Carter et al., 2020). In writing, critical overviews are usually more than 300 words because of a researcher’s critique.

Highlight

If scholars want to capture an attention of a target audience to a study through a particular use of leading statements, they use highlight overviews. In turn, this form of a paper’s summary has limited applications in academic writing (Hyatt & Roberts, 2024). As a result, an entire content distinguishes various types of abstracts.

Format

| Section | Content |

|---|---|

| Title | Presents a title “Abstract” in bold. |

| Context/Background | Provides a brief context or background for an entire study and its writing. |

| Introduces a general topic and a significance of a further examination. | |

| Objective/Purpose | Clearly states a main goal or purpose of a presented document. |

| Describes what a given study aims to achieve or a problem it addresses. | |

| Methods/Approach | Summarizes a research methodology or approach. |

| Briefly explains how an entire study was conducted or the methods used to gather data. | |

| Results/Findings | Highlights the key findings or outcomes of a whole examination. |

| Presents the most significant results of a given study. | |

| Conclusion/Implications | Summarizes main conclusions drawn from a research paper. |

| Discusses broader implications or significance of the findings. | |

| Keywords | Lists 3-10 terms related to a research paper for indexing and searchability purposes. |

| A particular term, such as “Keywords,” must be italicized and ends with “:”. |

Note: Some writing sections of an abstract can be added, deleted, or combined with each other, depending on paper’s requirements, scopes of analysis, and complexities of topics. For example, a basic abstract format is a structured summary that briefly presents key components of a research paper, including a purpose, methodology, results, and conclusions, typically in a concise and standardized manner (Hyatt & Roberts, 2024). Basically, the word “abstract” refers to a summary of main points of a larger work, or it can describe something that is conceptual, theoretical, or not tied to physical reality. Further on, the IMRaD structure is a format used in scientific writing that stands for introduction, methods, results, and discussion, organizing an entire content of research papers systematically (Carter et al., 2020). In writing, the 4 C’s of an abstract are clarity, conciseness, coherence, and consistency. Moreover, scholars often use past tense in an abstract when describing the methods and results of an entire examination, but present tense can be followed for stating conclusions or implications (Burton, 2021). Finally, an abstract example is a brief summary that illustrates how a research paper’s key elements, such as a purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions, are organized into a single, concise paragraph. As such, the first sentence of an abstract introduces a research problem or objective, setting a stage for writing a document (Hartley & Cabanac, 2017). In turn, to start an abstract, people begin with a clear statement of a research problem or objective, setting a unique paper’s context for a further study.

Steps on How to Write an Abstract

To write an abstract, people concisely summarize a research problem, objectives, methods, key results, and conclusions in a single paragraph, ensuring clarity and brevity while capturing a research paper’s essence. For example, the five parts of an abstract are a background, objective, methods, results, and conclusion (Carter et al., 2020). Hence, basic writing steps include:

- Understand Requirements: Review course guidelines for word count, writing structure, and content specific to your assignment or publication.

- Start With a Purpose: Clearly state a main objective or question your study addresses.

- Summarize a Background: Provide a brief context or background to highlight an actual significance of a research paper and its writing.

- Outline a Methodology: Describe key research methods or approach you used to conduct an entire study.

- Highlight Key Findings: Present the most important results or discoveries made during your examination.

- Discuss Conclusions: Summarize main conclusions and their implications for a chose field of study.

- Use Concise Language: Write clearly and concisely, ensuring each word contributes to a summary.

- Avoid Detailed Explanations: Omit detailed descriptions, references, and unnecessary jargon to maintain brevity.

- Revise for Clarity: Edit an abstract page to ensure it is coherent, free of writing errors, and easy to understand.

- Include Keywords: Add relevant keywords to enhance a document’s searchability and indexing.

Formal Journals and College Documents

Abstracts in formal journals are somewhat different from college paper summaries due to discrepancies in their structures. For example, an abstract section in a dissertation may have additional elements (Hyatt & Roberts, 2024). In writing, they may not necessarily appear in a document but maintain fundamental components. Moreover, there are no significant differences between various college paper overview sections (Carter et al., 2020). Similarly, specific instructions provided by scholarly journals create different requirements. In particular, there are substantial differences between journal and college paper synopsis sections, which should include various main elements of this page (Burton, 2021). As a result, others may identify some irregularities, depending on a formal structure provided by a periodical.

Criteria

Strict adherence to provided instructions and unbiased representation of an entire work can improve an overall quality of a summary page. For example, to write an academic abstract, people concisely summarize a research’s purpose, methodology, key findings, and conclusions in a single, well-organized paragraph, adhering to any specific paper formatting guidelines provided (Carter et al., 2020). In writing, authors ought to be cautious concerning their choice of words. Further on, objectivity may be maintained by ensuring that whichever pieces of information appear on a summary page are not subject to misinterpretation (Hartley & Cabanac, 2017). In writing, periodicals do not provide much flexibility in formal structures. On the other hand, it may force some changes to an overview structure that scholars have to cover if they want to maintain consistency. Moreover, to end an abstract, people summarize main conclusion or implications of a research paper, highlighting its significance or potential impact (Carter et al., 2020). Basically, if students address main aspects of this part of a college research paper, improving an overall quality of a document requires a slight modification. In turn, some examples of sentence starters for beginning an abstract are:

- This case study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of … .

- A primary objective of this research paper is to explore a direct relationship between … .

- In this analysis, we present a detailed examination of … .

- This capstone project seeks to address key challenges associated with … .

- A primary purpose of this dissertation is to investigate underlying factors and elements that contribute to … .

- This report is focused on understanding how … .

- Our investigation examines potential effects of [variable] on [outcome], with particular attention to … .

- This thesis paper offers new insights into critical mechanisms by which … .

- This research proposal explores potential implications of [concept or theory] in a context of … .

- In this term paper, a central aim to shed light on complex interactions between … .

Abstract vs. Introduction

| Aspect | Abstract | Introduction |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To summarize an entire research paper, including purpose, methods, results, and conclusions. | To introduce a specific topic, provide background, and state a research question or hypothesis. |

| Length | About 150-300 words, depending on academic levels or institutional requirements. | Usually longer, ranging from a few paragraphs to several pages, depending on complexities of study topics. |

| Content | Provides a brief overview of an entire examination, including key points from all sections of a paper. | Focuses on background information, a unique problem being addressed, and an actual significance of a study. |

| Detail Level | Highly concise, only the most essential details are included. | More detailed, with explanations and context to set up a research question or hypothesis. |

| Structure | Typically a single paragraph in a standard structure but very condensed. | Multiple paragraphs, often with subsections, like a background, research question, and objectives. |

| Timing of Writing | Written after an entire paper is completed. | Usually written early in a research process but refined as a study progresses. |

| Audience | Helps readers quickly decide if a paper is relevant to their interests or investigations. | Engages readers by providing a unique context and convincing them of an actual importance of a given study. |

| Inclusion of Results | Briefly includes key findings and conclusions. | Does not include specific results but focuses on a specific rationale and purpose of a study. |

| Use of Citations | Rarely includes citations but focuses on a researcher’s work. | Often includes citations to a background literature to establish a unique context and overall credibility. |

| Searchability | Used for indexing and retrieval in databases. | Not typically used for indexing but serves as a foundation for understanding a research paper. |

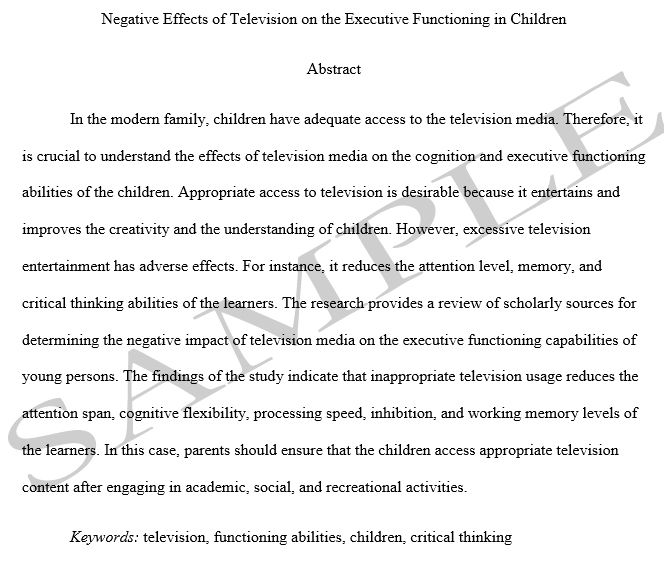

Abstract Example

What Examples to Include

| Example | Description |

|---|---|

| Research Problem or Question | Clearly state a specific problem or research question a presented study addresses. |

| Purpose or Objective | Explain a main goal or purpose of a paper, highlighting what a given study aims to achieve. |

| Methodology or Approach | Briefly describe some methods or approaches used in a study, including any key techniques or processes. |

| Key Results or Findings | Summarize the most significant findings or outcomes of a study, focusing on the core results. |

| Conclusions or Implications | Highlight main conclusions drawn from an entire examination and discuss their broader implications. |

| Significance of a Study | Describe an actual importance or relevance of a given project, explaining why it matters in a specific field. |

| Scope of Analysis | Define some boundaries or limits of a study, such as time, location, or specific subjects. |

| Theoretical Framework | Mention any theories or frameworks that underpin a whole investigation. |

| Research Gap | Identify a potential gap in existing knowledge or literature that a given project addresses, emphasizing a study’s novelty. |

| Keywords | Include relevant keywords to help with an indexing and searchability of a research paper. |

Common Mistakes

- Including Too Much Detail: Overloading an abstract with unnecessary details can make it confusing and hard to follow.

- Being Too Vague: Failing to provide clear and specific information can leave readers unsure about a study’s purpose or its findings.

- Neglecting Key Findings: Omitting important results undermines a summary’s ability to represent an entire paper accurately.

- Exceeding a Word Limit: Going beyond a specific word limit can result in a summary being cut off or rejected by journals or conferences.

- Using Complex Jargon: Overuse of technical language can alienate readers who are not experts in a specific field.

- Lack of Clarity: Writing in an unclear manner can make an overview difficult to understand.

- Ignoring a Purpose: Failing to clearly state a specific question or purpose can make a synopsis incomplete.

- Writing Before Completing a Paper: Writing an abstract before finishing a research paper can lead to inconsistencies and omissions.

- Including New Information Not in a Paper: Introducing content in a synopsis that does not appear in a research paper can confuse and mislead readers.

- Poor Structure: Lacking a logical flow or organization can make a synopsis hard to navigate and diminish its effectiveness.

Summing Up

By answering a question on how to write an abstract, this summary page is a must for any research paper. In writing, an abstract section has five principal aspects that have to be discussed for a quality text to be produced. Firstly, descriptive and informative summaries appear to be the most commonly used types. On the other hand, critical and highlight overviews may have limited application in academic research. Moreover, formal scholarly journal synopsis sections are mistakenly perceived to be superior to college paper summaries. However, this is not a case because there is a difference in a structure alone. In turn, a unique technique of authoring journal summaries can be improved by complying with specific instructions provided by different periodicals. Besides, people should avoid an intentionally biased presentation of any piece of information in their writing.

References

Burton, H. M. (2021). Your first research paper: Learn how to start, structure, write and publish a perfect research paper to get the top mark. Independently Published.

Carter, S., Guerin, C., & Aitchison, C. (2020). Doctoral writing: Practices, processes and pleasures. Springer Nature.

Drury, A., Pape, E., Dowling, M., Miguel, S., Fernández-Ortega, P., Papadopoulou, C., & Kotronoulas, G. (2023). How to write a comprehensive and informative research abstract. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 39(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2023.151395

Hartley, J., & Cabanac, G. (2017). Thirteen ways to write an abstract. Publications, 5(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications5020011

Hyatt, L., & Roberts, C. (2024). The dissertation journey: A practical and comprehensive guide to planning, writing, and defending your dissertation. SAGE Publications.

Miller, A. G. (2023). How to write an abstract for presentation at a scientific meeting. Respiratory Care, 68(11), 1569–1575. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.11101